Measure Your Effort, Not The Outcomes

Why time-based goals beat output-based goals.

TL;DR

- The Problem: Outcome-based goals (e.g., “finish project X”) are demotivating for complex projects because the required time and effort are unpredictable. This leads to stress and a feeling of failure, even when you’re working hard.

- The Theory: The best way to maintain motivation is to set milestones. The most effective milestones divide a project into chunks of equal effort, not equal progress. This means bunching milestones together during the hardest parts of a task.

- The Solution: For most projects, we can’t know the “effort curve” in advance. The most practical solution is to set time-based goals (e.g., “work for 5 hours”). Time is an excellent, controllable proxy for effort.

- The Result: This approach decouples your sense of accomplishment from unpredictable outcomes. It ties success to an input you control, leading to less stress and more sustainable productivity.

Introduction

This year, I changed the way I go about completing projects. I stopped setting outcome-based goals, and I started setting time-based goals. Surprisingly, this has not only improved my productivity, but it also lifted (some of) the stress of chronically feeling behind on everything.

It turns out there are good psychological reasons why my new method works better— and I so I thought it would be worth exploring why, and proving it with some math. Here’s a quick picture of how I used to plan for my week, and what would typically go wrong.

Plan for the Week:

- Finish draft of project X

- Add proof of Y result to project Z

- Complete referee report

- Finish first draft of slides for seminar and send to coauthor

On Monday, I start on the final section of project X. Simple enough. But as I write, I see a way to reorganize the project to make it clearer. That takes the whole day. Tuesday, I get to that “final section” again, only to find the final result isn’t as easy to prove as I thought. The reason? A stupid mistake I made in Section 1. Fixing it creates a cascade of revisions that eats up the rest of the week.

Fast forward to Friday afternoon: I feel like a failure, and I’ve got a stack of tasks that are dragging into next week. Kill me now. I’m exaggerating a little, but probably less than you think. This has happened to me more than once—it’s demotivating and it makes you feel like you’re not doing enough. In reality, you’ve spent hours upon hours engaging in focused, productive work, you just didn’t arrive at the outcome you had expected.

The core difficulty is that for some tasks, it’s impossible to know how long they will take. This is the daily reality of research, but it’s also true for things like starting a business or tackling a DIY project. To some degree its even true for improving your fitness or learning a musical instrument. The framework I’ll present reveals a core principle for setting motivating goals/milestones, which provides a new way to think about how to address this uncertainty. It can also be applied to more “concrete” goals, such as saving a certain number of dollars. But before we get to the theory, let’s talk about the psychology of goal-setting.

The Psychology of Goal-Setting

A huge part of that feeling of failure in my example above was a collapse in motivation. When a task gets unexpectedly longer, you get stuck in the middle, and the middle is a motivation dead-zone— all the joy of the project seems to get sucked out of you. There’s a name for this phenomenon: the “middle-slump.”

The middle-slump describes how our motivation on a long task follows a “U” shape: it’s highest at the beginning and the end of the task. This is a pattern documented in several studies (see, e.g. this paper). A compelling explanation for this phenomenon is an idea from behavioral economics called reference-dependence.

At the start of a project, your reference point is the beginning— you’re moving “away from zero”. Every step you take feels like a gain. But around the halfway mark, your reference point shifts— you start looking ahead to the finish line. When this happens, you’re no longer focused on what you’ve accomplished, but on the vast distance you still have to go. This switch feels like moving from a position of gain to a position of loss, and it can seriously dampen your motivation.

So how does one overcome the middle slump? I think the most powerful way is to set meaningful milestones along the way towards the goal. A milestone might be something like “finish the introduction”, or “save $1000”, or “run 5km without stopping”. This might seem obvious, but the reason it works is that it anchors your reference point in things that are closer to your current level of progress, so you’re never overwhelmingly demotivated by a far-away finish line.

But there’s a trade-off: set milestones that are too close together, and they cease to be meaningful; set them too far apart, and you’ll face demotivation. So how do you work out how to set milestones? And how does this connect back to my opening idea of “time-based” goals? To answer that, we need a little bit of math. And to save those of you who aren’t interested in the math, I’ve relegated my model to the very end (see the addendum on a theory of milestones).

The Equal Effort Rule

The punch line of my model is the following:

The equal effort rule: Milestones should be chosen so as to equalize the total effort exerted between consecutive milestones.

Let’s start by talking about what this means in practice, and then we’ll get to the idea of time-based milestones.

How effort costs determine optimal milestones

So how do we apply the equal effort rule to set optimal milestones and beat the middle slump? You might intuitively think that we should space them evenly, say at 25%, 50%, and 75% of the way through a project. But this is often the wrong approach.

The reason is that not all parts of a project are created equal. Think of a project as a journey. Some parts are a leisurely walk on flat ground, while others are a difficult uphill climb. The flaw in evenly-spaced milestones is that they ignore the changes in the terrain. A milestone at “50% complete” might leave you facing the single hardest part of the project, a recipe for demotivation.

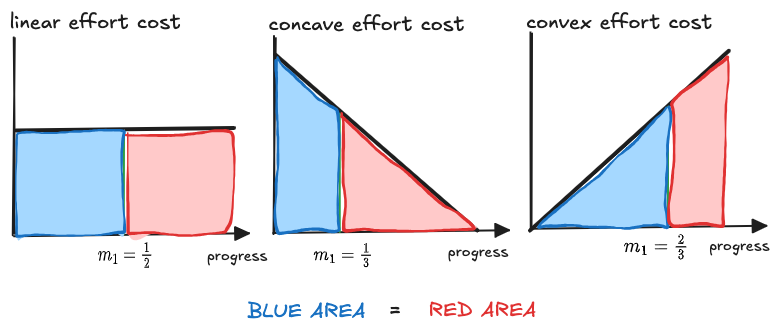

The goal of a milestone isn’t just to mark progress; it’s to break the journey into stages that feel psychologically manageable. The most effective milestones, therefore, are those that divide the project into chunks of roughly equal effort. Consider the three examples below of setting a single milestone $m_1$.

When effort cost is constant… Some projects require steady effort throughout. Think of writing a 10-page report where each page is similarly difficult. Here, the “effort curve” (which I define in the model) is flat. This means the total effort grows linearly. To divide the effort into equal chunks, you should set evenly spaced milestones. (e.g., at $m_1=50\%$)

When a project gets harder over time… For me, this is what happens in a research project. Early progress feels fast, but as you get into the weeds, each percentage point of progress requires substantially more work. The effort curve is increasing, so the total effort is convex. The “equal-effort” rule says you should bunch your milestones closer together near the end. This is the $m_1=\tfrac{2}{3}$ example above— it breaks the final push into a more manageable step.

When a project gets easier over time… This happens with tasks that have a high setup cost. Imagine a DIY project where you spend the first day just buying and setting up all your tools. Once you start, the actual work is quick. Here, the effort curve is decreasing, so total effort is concave. The rule says you should bunch your milestones at the beginning to get you through the initial administrative or setup hurdles. This is the $m_1=\tfrac{1}{3}$ example above.

From Equal Effort to Time-Based Milestones

This all sounds great, but how can you possibly know the shape of your project’s effort curve in advance? Even worse, how can you possibly know how exactly how far along your progress is? Most of the time, you can’t.

Trying to set milestones based on a percentage of completion (e.g., “Finish the first draft”) for these tasks is precisely what leads to the failure mode I described in the introduction. You are anchoring on an outcome whose position is unknown.

And this brings us back to the simple idea from the introduction: setting time-based goals.

Think about what a goal like “Spend five hours working on Project X” represents. It is, in essence, a goal to expend a fixed amount of effort. Time is the universal input. Unlike progress, it is perfectly measurable and entirely within your control.

By setting time-based goals, you can execute the optimal strategy while completely circumventing the need to know how long any step in the project is going to take you. Crucially, if your effort is constant over time, then you are, by definition, creating milestones according to the equal effort principle.

The goal is no longer to reach an uncertain destination (as is the case for outcome-based goals like “Finish the draft”), but to travel for a set amount of time. This approach allows you to consistently recognize the value of the work you put in, and completely neutralizes the demotivating trap of an outcome that’s further away than you thought.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this post, I described a familiar cycle: setting ambitious goals, getting derailed by unexpected complexity, and ending the week feeling like a failure. The problem wasn’t a lack of effort, it was a flawed framework for measuring success. An outcome-based to-do list makes our sense of accomplishment fragile— we hold ourselves hostage to a future we can’t possibly predict.

The journey we’ve taken shows there’s a better way. By understanding the psychology of the “middle slump,” we see why we need milestones to stay motivated. With the help of some math, we see that the most effective milestones are those that divide a project into chunks of equal effort, not equal progress.

But the final, crucial insight is that for most complex work, this “optimal” plan is impossible to map out in advance. And this leads us to the solution: time-based goals.

What this all amounts to is a pivot from asking “What will I finish?” to “How long will I spend on this?” This isn’t just a semantic game; it reframes the entire endeavor. It makes your sense of success robust to the uncertainty that derailed my week in the introduction. The work’s inherent difficulty becomes a property of the task, not a measure of your effectiveness. You learn to value the effort itself, because the effort is what is actually under your control.

If you recognise the feeling of that week—of being “productive” yet feeling like a failure—I can only suggest trying the method. For a single week, trade your list of outcomes for a schedule of effort. Decide on Monday how many hours a given project deserves, and then work those hours. The goal is no longer to ‘finish the draft’; the goal is to ‘work on the draft for five hours’. For me, this change didn’t just improve my productivity; it lifted the chronic, low-grade stress of feeling perpetually behind on everything. I hope it does the same for you.

Addendum

To see how to set the right milestones, let’s build a simple model of a task or project.

Progress and Effort

Let $x_t\in [0,1]$ denote the proportion of a task completed at time $t$. Making progress requires exerting effort, which is costly. We can allow for the marginal cost of progress to vary across the task by defining a cost function, $c(x)>0$. For some projects, the initial stages are the hardest (high $c(x)$ near $x=0$), while for others, the final push is the most demanding.

The cumulative effort required to reach progress level $x$ is therefore the integral of these marginal costs:

\[E(x) = \int_0^x c(s)\,ds.\]Motivation: Reference Points and Costs

Now, we can model the agent’s motivation at any point in time. The Psychology of Motivation suggests that motivation is enhanced by proximity to a goal. Let’s combine this with the cost of effort.

At any point $x$, the agent is aware of the set of reference points $\mathcal R={0}\cup M\cup{1}$ which includes the start, the end, and any milestones $M={m_1,\dots, m_n}$. Let $d(x) = \min_{r\in\mathcal R} \lvert x-r\rvert$ be the distance to the nearest reference point.

We can model the “motivational boost” $\mu$ as a decreasing function of this distance: $\mu(d(x))$. The net utility from making progress, or the “instantaneous motivation”, is the difference between this boost and the marginal cost of effort:

\[MU(x)=\mu\left(d(x)\right)-c(x).\]Without milestones, the farthest you will ever be from a reference point is in the middle of $0$ and $1$, i.e. at $x=1/2$; hence $MU(x)$ dips there— this is the middle slump.

Suppose that if your motivation drops below a certain level, you’ll abandon the task. So your objective is to keep the “motivation floor” as high as possible.

What a milestone does

Suppose we insert a single milestone $m$. The farthest point from any reference in the two resulting segments is now $\max\{\frac{m}{2},\frac{1-m}{2}\}$. Because motivation drops with distance, the longest gap between consecutive milestones sets a ceiling on how low motivation can sink. So keeping the motivation floor high means shrinking the longest gap between consecutive milestones—well, almost.

The motivation over an interval $I_k \equiv [m_{k},.m_{k+1}]$ also depends crucially on how hard each bit of progress is: an additional percentage point of progress at 80% completion may require a lot more effort than the first 1%. For “nice enough” cost curves $c(x)$ (e.g. continuous, monotone), the hit to motivation on $I_k$ is bounded below by a term that grows with

\[\Delta E_k \equiv \int_{m_{k}}^{m_{k+1}}c(s)\,ds.\]So motivation is at its lowest in the segment with the largest $\Delta E_k$. To keep motivation as high as possible, we minimise that largest effort cost:

\[\min\max_k \Delta E_k.\]To do this, one simply chooses milestones which slice the effort curve into $n+1$ equal areas: (this is the “minimax” solution):

\[(\Delta E_k =) \,\,\,\, E(m_k)-E(m_{k-1}) = \frac{E(1)}{n+1}, \quad k=1,\dots, n+1.\]with $m_0\equiv0,\;m_{n+1}\equiv1$. I call this “the equal effort rule”.