AI is turning us into proof-checkers, not proof-writers.

In a world where AI can write proofs, the real skills are asking the right questions and having a deep intuition for the answers.

Introduction

There’s been some noise recently about the value of LLMs for mathematical research. It was not at all clear back when ChatGPT-3 was the frontier model that LLMs were going to have utility beyond writing emails or editing essays. Nowadays, ChatGPT Pro is a fully-fledged research assistant, only better. The benchmarks are already unbelievable: just last month, the DeepSeekMath-V2 model scored 118/120 on the 2024 Putnam competition. For context, this is higher than the highest score of the 90 human participants

Benchmarks are one thing, but actual research is another. If the numbers don’t convince you, perhaps a Fields Medalist will. Terence Tao recently described how he used ChatGPT Pro to flesh out a counterexample to a conjecture. Back in August, mathematician Sebastien Bubeck shared how he solved an open convex optimization problem using ChatGPT Pro. And the improvements keep coming: according to Daniel Litt, ChatGPT 5.2 Pro (released last week) represents a “step change” in usefulness for algebraic geometry and number theory.

If leading mathematicians are outsourcing some thinking to an LLM, what does this mean for the future of research?

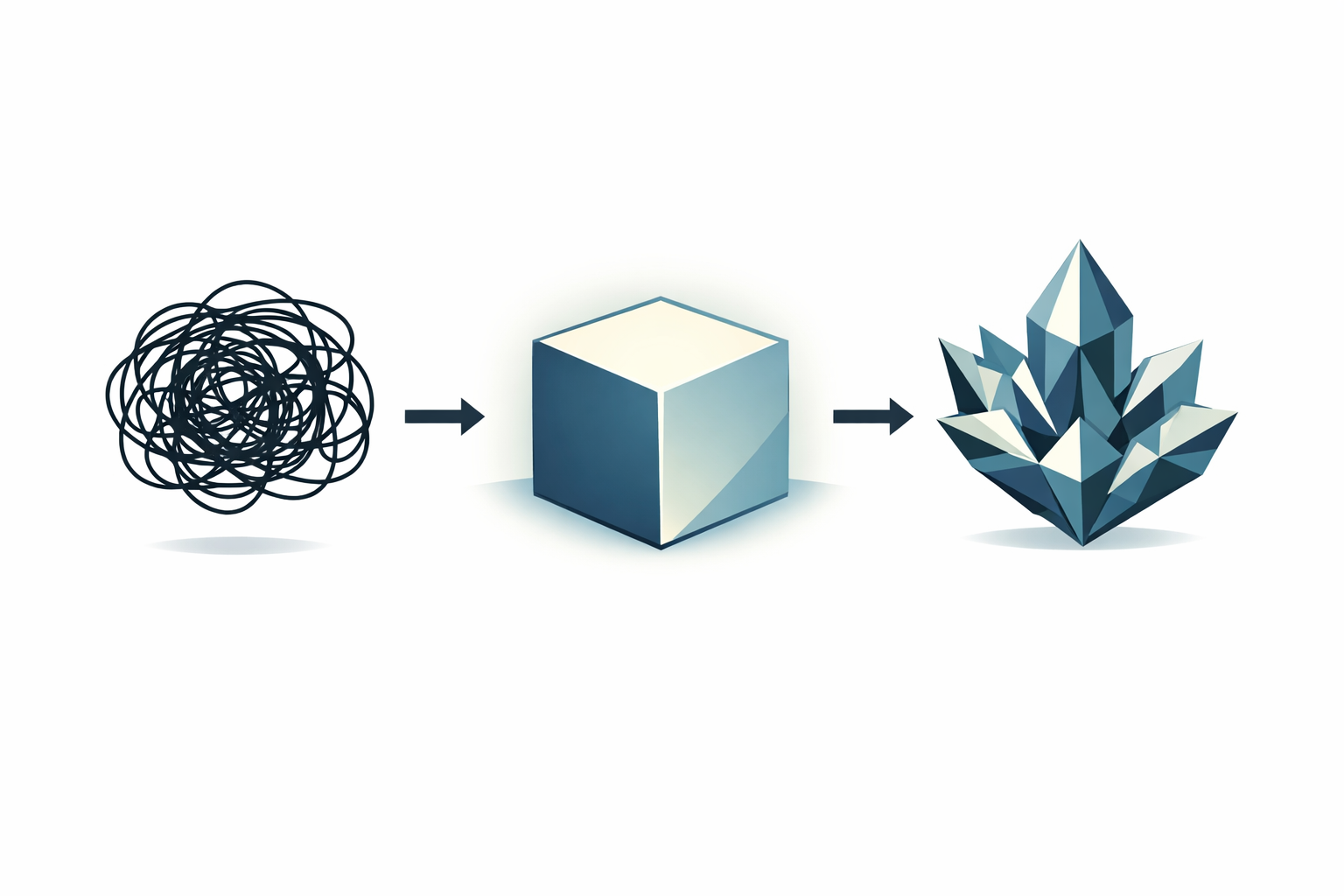

From Proof-Writers to Proof-Checkers

In my own research ChatGPT Pro has been invaluable, but using it effectively has required a change in my workflow. For example, in my recent paper Controlling Complex Contagions I was stuck on a particular proof which I gave to the model. As I stepped through its working, I noticed a mistake. I pointed out the mistake and it tried again. Five times we went through this loop until finally, I could find no more errors. The proof was correct.

Essentially, my role shifted from being a writer, to being a checker. This represents a huge productivity boost, but proof-writing and proof-checking are different skills. Good proof-writing requires technical skills and creativity. Proof-checking, on the other hand, requires attention to detail, patience, and skepticism. They’re complementary skills, but they are different. There is also a risk that the shift is not benign: early evidence suggests that fully outsourcing the creative work to AI can weaken understanding.

Of course, in a world where researchers are proof-checkers rather than proof-writers, the ability to write technically challenging proofs becomes less valuable. An important question then is: which skills become more valuable? To answer that, we need some Economics. But first, I want to propose a thought experiment.

The Proof Machine

Imagine you alone had access to a machine which could immediately tell you the answer to any math problem you asked of it. You can ask as many questions as you like (this is not a “no wishing for more wishes” situation). What would you ask? “Solve the Riemann hypothesis”? “Does P=NP”?

I imagine once you’ve exhausted all the remaining Millennium Prize problems and moved through the Erdös problems, you might find yourself… bored. Why? Because when solving problems becomes easy, the binding constraint (there’s the economics) is no longer compute, it’s asking the right questions.

Asking the right questions has always been an important skill in research, but I think in the past one could mask a lack of vision with technical virtuosity (no, I’m not going to name names). In a world where solving problems is easy, the best researchers will be those who can formulate the most interesting, important, and novel questions.

It is worth noting that while this “Proof Machine” is still a hypothetical for frontier mathematicians like Tao, for the rest of us—economists, quantitative social scientists, engineers, and even many physicists—the machine is effectively already here. That makes what I am about to say even more pressing.

The Renaissance of Intuition

In many ways, this dynamic isn’t new. Senior professors have often operated as “visionaries,” coming up with the “good questions” and handing off technical grunt-work to graduate students. But the “Proof Machine” accelerates this pipeline by orders of magnitude. For professors with teams of RAs at their disposal, the essential skill remains asking the right questions. But for graduate students doing the work, the essential skill becomes efficient verification.

This brings us to what I think is the most important skill of the AI era: Intuition.

Terence Tao has spoken about the “post-rigorous” stage of mathematical development, where deep intuition guides you to the answer before you write the proof. He suggests that you develop this intuition by doing the rigorous grunt-work. The danger now is that if our students leave all the rigour up to AI, they might never develop the intuition required to efficiently check its working. The key for the next generation will be to use AI aggressively after they’ve built some intuition, not instead of it.

But for those who do have a good intuition, AI is a superpower. It allows us to skip over the minutiae and focus entirely on the structure of the argument—as someone who doesn’t like having to work through the details, this is my absolute dream come true. In this world, the best researchers will be the ones with the best “gut sense” of the truth. They are the ones who can look at a machine-generated proof and say, “That is technically correct, but it misses the point,” or “That result feels wrong, check the assumptions.”

The machine can drive the car, and it can steer around the potholes. But it lacks an internal compass. It doesn’t know when we’ve wandered into the wrong part of town, or if the destination is even worth visiting. That sense of direction remains, for now, a deeply human problem.

Conclusion

We are entering a golden age of research productivity, but it demands a retooling of our relationship with our work. If you treat AI as a substitute for your thinking, you will become a passive observer of machine-generated logic.

But if you treat it as a complement, you can shift your focus higher up the value chain. The researchers who thrive will be those who cultivate the patience to verify the machine’s work, and the taste to know which questions are worth asking in the first place.

The “Proof Machine” is here. Do you have the questions to keep it busy?

DJ